On April 17, 1975, the people of Phnom Penh celebrated in the streets as the Khmer Rouge soldiers marched into town. Finally, the rebels had ousted the corrupt, pro-American government and liberated Cambodia from the Viet Cong. At long last, there would be peace.

Little did they know that it was the start of a four year nightmare and suffering beyond their wildest fears. Only hours after Pol Pot and his comrades declared victory, teenage boys dressed in black and armed with rifles appeared everywhere. Anyone who didn’t fly a white flag outside their house was shot, and the ones who survived were chased out of town. It wasn’t safe to stay, they said. Another American bomb raid was due. They would be able to return in a few days. But it would take years until anyone could go back to Phnom Penh. All urban centers in Cambodia were turned into ghost towns, as the people of the Democratic Republic of Kampuchea were forced into slave labor in remote villages.

Had they known, people would surely have reacted differently. But after being caught in the crossfire between Vietnam and the United States for the last ten years, a peaceful revolution seemed to answer everyone’s prayers. The Vietnamese had used their army to control their weaker neighbor. And Nixon’s army had peppered the border areas of neutral Cambodia with over 500,000 tonnes of bombs to catch any possible Vietnamese who might have slipped across the borders, four times as many bombs as they dropped on Japan during the second world war. Almost 10% of the Cambodian population had lost their lives in a war that was not their own.

US Bombing of Cambodian areas 1965-1973

Khmer Rouge saw this moment as their chance to rise to power. With the aid of King Sihanouk, who had been exiled to China by the previous government, they presented themselves as the right choice for a free Kampuchea. They promised independence from Vietnam and thus an end to the bombings by the Americans.

But things didn’t turn out quite as planned. In an attempt to copy China’s agrarian revolution, millions of city-dwellers were relocated to forced-labor camps in the countryside. They were made to live in primitive huts and work the fields from dawn to dusk under the scorching sun without sufficient food or medicine. Schools were closed, hospitals and factories shut down. Banking, finance and currency were all abolished, and religions prohibited. Private properties were confiscated and all intellectuals, professionals, doctors, teachers and entrepreneurs were executed. Children were separated from their parents, and made to work as slaves in special children’s camps.

When the harvests didn’t increase according to plan, the food portions decreased to a few grains of rice in a watery soup and soon enough people started dying of starvation, exhaustion and diseases like malaria, dysentery and typhoid. Anyone who tried to supplement their diet with insects, rotten leaves or even rats was tortured or executed. Those who protested were shot.

It soon became evident that the revolution was a failure. Their idea of a completely self-sufficient Cambodia did not work. The Khmer Rouge responded by blaming it on others. Suddenly anyone could be accused for treason. Former friends of Pol Pot were no exception, nor were fellow revolutionaries. Anyone who was suspected of anti-Kampuchean activities was brought into prison and tortured until he confessed that he was working for the CIA or KGB, or – remarkably – both. Every “traitor” was forced to name up to fifty other co-conspirators. And so the list of innocent “criminals” grew by leaps and bounds until almost no one was safe. And everyone finally admitted to some crime, only to make the torture stop.

An abandoned school in the deserted capital Phnom Penh, proved an ideal site for a prison for these “traitors”; the Tuol Sleng prison camp, also called S-21. Here, in a blocked off area of several square kilometers, the Khmer Rouge tortured and executed their “enemies” in secret. Former class-rooms were divided into tiny cells, so small that a grown man could not stretch out his body on the floor. The prisoners were chained to the floor, and forbidden to speak or make any noises. A plastic can was brought in as needed to be used as a toilet. Other classrooms were filled with prisoners, laying side by side, chained to the floor. Food was provided once a day at the most, and consisted of a couple of spoonfuls of rice and water. Bathing occurred once or twice a month, by the guards hosing water through the classroom windows.Every night, teenage guards who had been taught torture methods on animals, took someone away to be tortured or executed. Screams were heard across the playground, when the prisoners were hung upside down and whipped until they passed out. Other methods included pulling of nails, cutting off fingers and near-drowning. Babies were taken from their mothers and shot or bludgeoned to death.

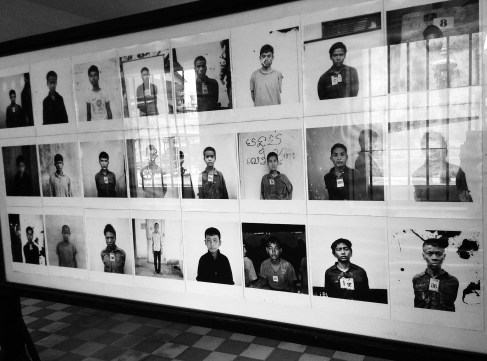

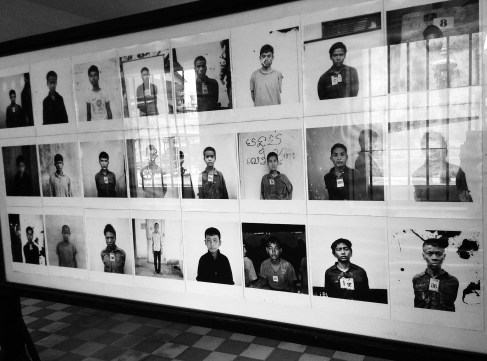

All 20,000 prisoners were photographed on admission to S-21.Their photographs still hang in the Tuol Sleng museum as silent reminders of the children, men and women that were tortured to death in this camp. The fear in their eyes is haunting. They all knew that imprisonment equaled death. No one was ever released. To this day, Cambodians are still identifying relatives or friends from the photos, and will finally know for sure what happened to them after they disappeared.

In 1979, when the Vietnamese army liberated Phnom Penh, only twelve of the tens of thousands of prisoners had survived. Some tortured bodies still lay rotting in their cells, but most had been buried a few miles away, at Choeung Ek the “enemy “dumping ground known as the Killing Fields.

In their four years of power, the Khmer Rouge murdered around two million people, or a quarter of the country’s population; mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers and children. Not one family remained intact. Still, the leaders of this organization who had committed war-crimes as heinous as those of Hitler or Stalin, remained on free foot for the next 28 years, supported economically and politically by the United States, China, Thailand, Britain, and the United Nations. Hiding in the Cambodian forest and continuing to terrorize the villages and towns of Cambodia, the UN named Khmer Rouge the “government of Cambodia in exile,”and allowed them to rule over the victims of their genocide for another fourteen years, until Vietnam withdrew from Cambodia.

Because of the support they received from their prosperous allies and international relief organizations, the Khmer Rouge flourished in hiding for decades until December 1998, when the organization was finally dissolved due to internal struggles. But before the Cambodians and International Leaders finally got their act together in terms of bringing these mass-murderers to trial, Pol Pot passed away, still as a free man, in April 1998. By 1999, the majority of the members had either surrendered or been captured.

How is it possible that a world that promised “never again” after WW II could turn a blind eye and even help these murderers get away with it? It all has to do with politics. The United States’ partnership with the Khmer Rouge grew out of their defeat against the Vietnamese. In this blind hatred, they formed an anti-Vietnamese and anti-Soviet partnership with China, and therefore supported the Khmer Rouge to help destabilize the pro-Vietnamese government in Cambodia.

But really, there is no excuse for the world’s response and behavior in regards to Cambodia. Two million people died under horrific circumstances. The survivors lived in terror among landmines and Khmer Rouge attacks for another fifteen years. Not until 2010 was any of the leaders charged. The trials against the only two surviving leaders of the Khmer Rouge are still ongoing in 2013. To this date, only one of the Khmer Rouge leaders has been sentenced. No one else has paid for their crimes.

The world has not learned anything from history. Why is it so difficult to put politics aside when we are dealing with murderers? Communism may be bad, but surely genocide is worse? When will the “free world” start acting morally?

Never again.

Please.